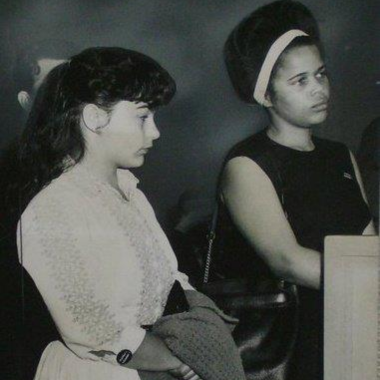

Photo: Art Frisch, San Francisco Chronicle, March 8, 1964

Kipp Dawson & Social Movement Resiliency Since the 1950s

Kipp Dawson built coalitions for over 60 years in some of the nation’s largest movements for freedom and equality. Her astonishing career stretched from the frontlines of the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam anti-war movement, to the women’s movement, gay liberation movement, labor movement, and education justice movement. As a lesbian, Jewish, working-class woman from a multi-racial family, Dawson illustrates the ways in which historically marginalized people have often engaged in collective action for change.

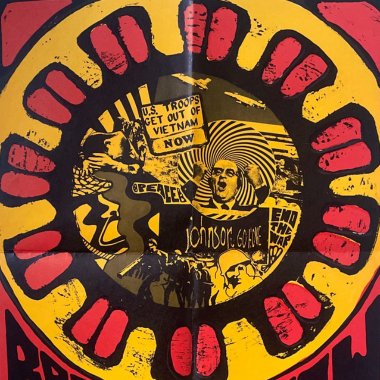

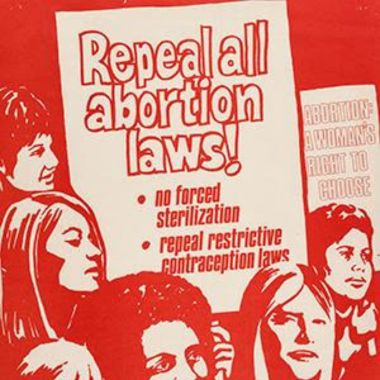

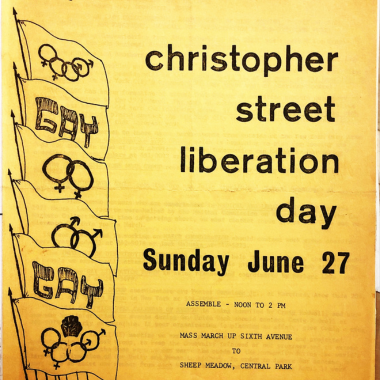

Dawson co-founded the first Civil Rights club at Berkeley High School, whose leaders went on to organize the major sit-ins that desegregated employment practices in San Francisco. She co-led the Free Speech Movement, coordinated some of the largest anti-Vietnam war demonstrations of the era, and helped plan the enormous Women’s Strike for Equality in New York City as well as the Christopher Street Liberation Day events following Stonewall, which became the annual Pride Day parades. Dawson served on staff for the Women’s National Abortion Action Coalition in the lead-up to Roe v. Wade, worked to desegregate schools in Boston, and ran as the Socialist Workers Party candidate for Senate from New York. She was arrested six times for protesting and spent a month in prison, was harassed by the FBI from childhood, named as a subversive by the House Un-American Activities Committee, and worked on the lawsuit that eventually helped expose the government’s COINTELPRO operations. After moving to Pittsburgh, Dawson worked as a coal miner underground for 13 years, supporting union organizing across the U.S. and internationally, and then taught public school for 22 years.

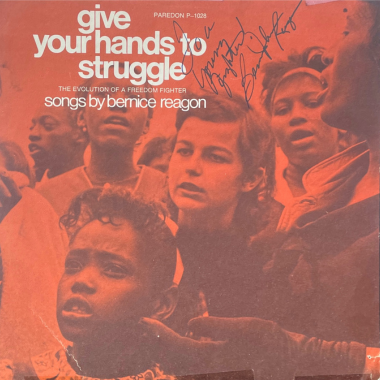

Photo: Kipp Dawson Papers, Box 7, Folder 11

The remarkable breadth and depth of Dawson’s intersectional, feminist, and highly cooperative activism suggests a rethinking of leadership within social movements as “women’s radical collaboration.” This framework reveals the often-invisible labor of women engaged in an intentional, transformational, and diffuse form of leadership. Radical collaboration prioritizes relationship building, creates networks of care, and redefines movement goals – all of which promote resiliency in the face of the very real dangers inherent in movement organizing. As Dawson and her collaborators well knew, the high stakes for their work included loss of life, liberty, livelihood, reputation, friends, colleagues, and careers. There were lower-stakes, too, including personal burnout and movement fatigue from long unpaid hours working for change that was slow to come, or incremental in ways that was hard to appreciate in the moment, with few big, obvious wins.

To form durable and robust movements that could survive and even thrive despite nearly constant losses, state-sponsored oppression, and violent resistance, Dawson and her fellow activists drew strength from the bonds of love, a deep sense of joy, and a shared vision for an alternative future. Dawson makes these connections explicit, saying, “the story of my life is a love story. And it’s a love story – a passionate, very passionate – love story between me and the work, to come together with other people to make this planet what it should be for all the life that is on it, and for the children who are going to be born.”1

Dawson points to a quote from the revolutionary Che Guevara, explaining movement work as “the Big Love” that keeps going:

Click the video to the left to watch Dawson describe her mother’s spiral theory and use the links below to explore StoryMaps highlighting the crucial role of love, joy, and hope in building movement resiliency.

citations

[1] Dawson interview, 3-23-2022

[2] Ibid.

[3] Dawson interview, 4-20-2022

[4] Dawson interview, 4-6-2022